Long Island Drinking Water and Contaminants

Take a sip and think. Where does your drinking water come from?

Water from every tap, fixture, and faucet on Long Island is pumped up from underground aquifers despite being surrounded by water. The very lifeforce of Long Island is contained within these underground reservoirs, but very few people actually know how these function or how they are affected by industry.

National Geographic defines an aquifer as “a body of rock/ sediment that holds groundwater,” and Groundwater is defined as “precipitation that has infiltrated the soil beyond the surface and collected in empty spaces underground.” The Long Island aquifer is an unconfined aquifer, which lies beneath a layer of permeable soil, compared to a confined aquifer with a layer of consolidated rock above. The three principal Long Island aquifers, the Upper Glacial aquifer, the Magothy aquifer, and the Lloyd aquifer, are composed of layers of sand and gravel deposited by glacial movement some 10,000 years ago. Thin layers of clay separate each respective aquifer. These aquifers are all replenished by regular precipitation, with the sand and gravel helping filter the water as it settles. The Magothy aquifer is the largest and most utilized by the Long Island population, supplying nearly 400 million gallons of water to 2.8 million people daily.

The water within the aquifers can be accessed in one of two ways. The first is natural processes, where the water table, or the level of water contained within the underground aquifers, is above the ground. This allows the water to seep into divots or onto lower ground forming natural freshwater rivers and lakes like Lake Ronkonkoma. The second way is to drill into the ground and build wells to process, treat, and pump water to the surface.

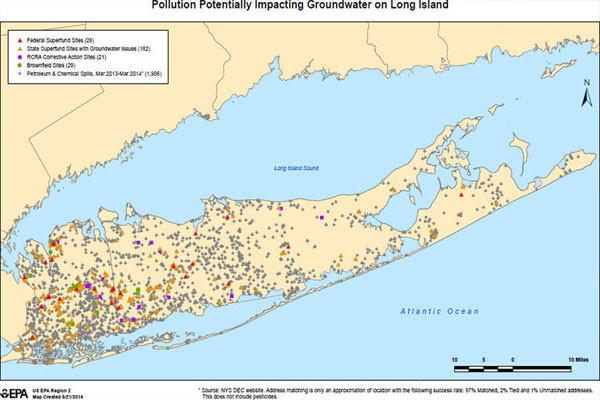

However, pollution has seeped into Long Island’s aquifers, polluting drinking water and putting public health at risk. Pollution can find its way into the underground aquifers through various means. The most common is runoff. This is where pollutants in the atmosphere and on the ground are carried off in the rain into the different aquifers beneath the ground. Another prominent polluter of Long Island’s drinking water is the erosion of storage tanks and pipes. As these erode, chemicals in the linings, paint and constructed material dissolve into the drinking water carried off to your home. Long Island faces explicitly unhealthy levels of iron and 1,4- Dioxane in its aquifers. Detected iron levels in Long Island’s drinking water are, in some places, three times the state limit, with excess amounts being traced to natural forming iron and iron-containing compounds in the aquifer rock. This may seem like a significant issue, but Long Island has invested much in the way of filtering out and removing the iron from its water supply before sending it to consumers. 1,4-Dioxane, on the other hand, is much deadlier. 1, 4-Dioxane is a colorless, organic liquid found in paints, varnishes, various soaps, adhesives, and antifreeze. In some areas of Long Island, typically in Suffolk County, the levels of 1,4-Dioxane are far past 150% of the recommended limit. Other areas’ levels of 1,4-Dioxane are dangerously close to the limit. The health effects of prolonged ingestion result in irritation of the nose, throat, lungs, and liver and kidney damage. 1,4-Dioxane has also been classified as a probable human carcinogen by the Environmental Protection Agency. However, despite the high amounts of 1,4-Dioxane, better filtration systems are unlikely to be implemented as Long Island falls short of the required funding by a whopping 482.5 million dollars.

What can you do to help? The first step is to get informed. Contact your local water quality control agency and find out what pollutants are present in your drinking water and what your local government is doing to remedy issues. It’s better to be informed of what you are putting into your body. Once you are notified, you can take action. Talk to your representative, petition, and inform and rally others. Suppose you want to take a more direct role in preventing runoff pollution. In that case, you can consider buying eco-friendly fertilizers, paint, or other chemicals likely to be washed into the aquifers when it rains—direct water streams caused by precipitation into more heavily vegetated areas to increase filtration or plant more greenery.

We all must do our part in protecting Long Island’s vital underground water reservoirs. We need them to survive!

Comments

Post a Comment